Personal and Global Polarities

Sometimes, the toughest challenges on the planet are simply waiting for the appropriate framing.

Recognizing some complex problems as polarities gives you powerful sense-making tools for navigating challenges that have no right or wrong answer.

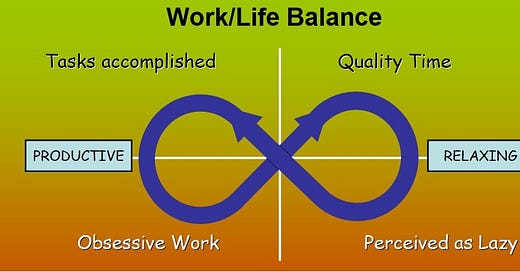

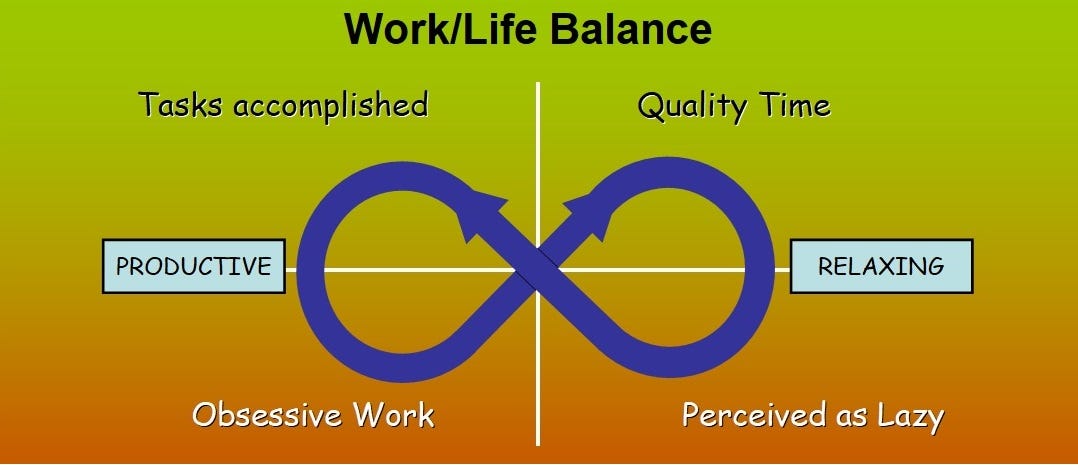

Have you sometimes wished that you were more productive? Perhaps you would like to write more Substack articles or invest more time going a over and above in the workplace. Every once in a while, while you’re feeling that way, some inspirational event might come your way that spurs you into action, and isn’t that great? You pour in the energy, make real progress, and promise yourself the discipline to keep it going.

And what if that worked? Or, what if that discipline created a productivity that bordered on obsession? Not much fun there. Everyone needs a break and a time to recharge their batteries. A bit of self-care. There’s more to life than work, right? So you back off; you spend more time with family and friends, or just chilling in front of the big screen.

But then a few weeks go by and you think: I should really be more productive…

There are plenty of articles out there on work/life balance. The important point to realize is that, in any given moment, there is no ‘balanced mix’—you are either working or resting. It’s just like breathing. Sometimes you need to inhale oxygen; at others you need to exhale carbon dioxide. You will never have the perfect ‘balance’ of gases that allow you to stop breathing. The ‘balance’ consists of spending time at one pole when that provides values, and then spending some time at the other pole when the value at the first drops off.

These are polarities—challenges consisting of two diametrically opposite poles where neither side is the ‘correct’ side. Instead, the key is to move between the two.

Recognizing some complex problems as polarities gives you powerful sense-making tools for navigating challenges that have no right or wrong answer. I’ve mentioned polarities before, in my post on Numbers and Happiness. I find the Polarity Management model, written up by Barry Johnson in his 1992 book of that name, to be very useful. (Johnson not only gives a thorough introduction to what polarities are, he also explores strategies for maximizing outcomes when faced with such challenges.)

The concept of polarities is very important to any exploration of the Value Crisis for two reasons:

A Polarity of Value Systems

The basic situation is that individuals and society now encompass two different categories of value systems: qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative values are intrinsic to everything in Nature and innate to every living thing—especially us. (Hunger, happiness, and integrity are not quantified—they are felt.) Quantitative values are an entirely number-based human construct (such as money or votes), where (by definition) more is Always better. These two categories can be considered polar opposites, such that we are constantly using one type or the other to make decisions in our lives. Within the context of our civilization, neither type of value is better or worse than the other; we require and use both all the time.

The value crisis does not arise from having two contrasting value systems. It is caused by society designating just one category (quantitative values) to have absolute precedence as the measure of success. As a result, the principle that More is Always Better pervades all key decisions, and the idea of peak sufficiency no longer mitigates our actions or environmental impacts. We adopt obsessive pursuits of unending growth, and the qualitative values of well-being, justice, and joy become expendable afterthoughts.

Again, qualitative values are not superior to their number-based complements, but, like any polarity, both sides must be respected and employed in equal measure. In an earlier post on happiness, I described what happens when we become fixed on one side of a polarity.

Qualitative Values as Polarities

The second most important use of polarities in my work is a bold and potentially groundbreaking assertion that I make about qualitative values. To get there, let’s consider an attribute of quantitative values for a moment.

Since they are entirely measured by number, changes in quantitative values over time can be easily graphed as a line. We are quite used to the up and down sawtooth of GDP, the exponential curves of population or energy usage, and the downward depreciating retail value of a car over time. So how do you graph qualitative values? True, they are not quantified, but they still go up and down—if you consider justice as a value, it’s quality does quite perceivably go up and down.

When might justice become injustice? That depends. Perhaps it is being too strict, or, perhaps it is too lenient. So, I say, justice must combine mercy and stringency—two polar opposites. Furthermore, I suggest that we can never define the perfect balance of those attributes. It is more of a dynamic dance that will change with circumstances and social norms. In other words, a polarity!

To consider more examples, religious faith can be thought of as existing within a polarity of an omniscient creator with an immutable master plan versus followers with free will; artistic beauty works as a polarity of simplicity versus complexity. I propose that all qualitative values can be mapped as a polarity of two opposites.

This principle helps to underline the fact that qualitative values are messy; they require some effort; they are non-standard; and they change constantly. Those are difficult attributes to build a civilization on, compared to number-based values which have none of those characteristics. Are you beginning to appreciate more and more where our value crisis originates?

So, it is not just qualitative values that can be expressed as a polarity—the conflict between qualitative and quantitative value systems is also a polarity. This awareness is critical if humanity is to make progress on its present challenges.

To close with where we began, I suspect that for many people, the search for work/life balance might actually by a small microcosm of the all-encompassing value crisis concept that I introduced more than a decade ago. Quite often, the work goals are getting that raise, meeting quotas and targets, or just being ‘productive’ in a countable way. Meanwhile, life goals are aimed at being more relaxed, taking care of health, and spending quality(!) time with others. If there is no all-or-nothing solution for ourselves, why should we adopt one for society?