It's Not About the Money

(Okay, it's not JUST about the money.) Teasers for the science of the Value Crisis.

A discussion about number-based values goes way beyond the addictive properties of money. It addresses the way those values actually work, their incompatibility with the natural world, and even hardcore science.

My overview of the Value Crisis is deceptively simple. Sometimes I worry that people just look at the premise and think: “Okay, sure—the author thinks we’re all too fixated on money. Fine. And his alternative is…? Not a lot of real world relevance to this discussion. Money makes the world go round. Ain’t no way society is getting rid of money.”

Hmm. Perhaps I’ve oversimplified my messaging.

The value crisis is not about individuals loving money or chasing wealth. Nor is it about corporate greed—something which I claim does not technically exist. Both of those are very real issues, but they are mere symptoms of the real problem.

My field of study concerns the measurement of successfulness by number. Sure, monetary wealth is the easiest example, but it’s not the only one. There’s also votes, followers, likes, views, utilitarianism (the greatest good for the greatest number), GDP, and market indices. These are all valued quantitatively, where more is always better.

It is worth noting again that “More is Always Better” is not the same thing as greed. Greed is when sufficiency is wantonly exceeded. However, if your value system does not have a concept of peak sufficiency (where more is not better), then it becomes problematic to define that pursuit as greed. (It’s a subtle point. Perhaps choosing a number-based value system indicates a propensity for greed, but within that value system, it is not considered greedy to take more—that’s just business.)

Generally speaking, ecological economists are more concerned about growth than greed. (This year’s conference of the International Society for Ecological Economics in Oslo is paired with the 11th International Degrowth conference.) The idea that economic growth, based on the finite resources and energy of a world where all life (including ours) exists in a delicate and complex web, can grow exponentially forever, suppressing all negative feedback – well, that’s not going to happen.

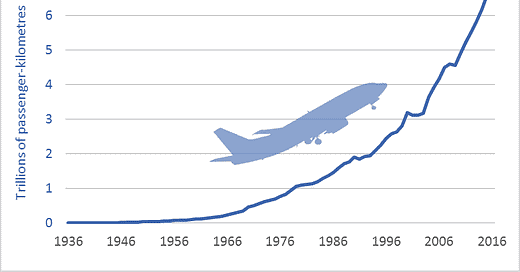

Here’s a thing about growth that most people just don’t get. We’ve all seen those charts with increasing exponential curves, where the graph is fairly flat for a long time and then suddenly appears to shoot up. In much of Nature, that kind of exponential shock to balanced cycles is often considered a bad thing, and is usually followed by an equally dramatic plummet. Proponents of our economic status quo might say that’s not the kind of growth they want. They are more in a favour of a gentle straight line increase, gliding upwards into an idyllic future. And yet the growth that they speak of is always a percentage. “The economy has to growth by x% in order to be healthy.”

Math news flash: Any consistent rate of growth IS exponential. Even a 3% growth rate doubles the total about every 23 years. And if you keep doubling a value, its history will produce the familiar graph line shooting up. (All that talk about detecting a cancerous growth early? That’s what they’re talking about.)

“The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.” – Albert A. Bartlett, physicist

So, a discussion about number-based values goes way beyond the addictive properties of money. It addresses the way those values actually work, their incompatibility with the natural world, and even hardcore science.

Exhibit “A” - I present the work of Frederick Soddy, a Nobel laureate chemist. In 1926, Soddy published Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt. Why would a chemist write a work on economics? One of the things that Soddy did was explore the relationship of money to the Laws of Thermodynamics. In physics, matter and energy cannot be created from nothing. But money is created from nothing all the time—that’s been a foundation of our banking system for hundreds of years (and perhaps a topic for a later essay).

He also studied the exchange of money for goods. Physics states that entropy increases over time for physical objects. The simple version of this is that food is consumed or rots and appliances gradually fall apart. Their functional value therefore decreases over time. However, money does not lose its nominal value over time. Indeed, if you take interest into account, monetary balances increase in value. Soddy saw this as a problematic disconnect between material goods and the money being exchanged for them. Such transactions were patently unfair.

To honour the theme of this post and go beyond the world of money, let’s look at a more remote example of quantitative values that I listed above: utilitarianism. One classic exploration of this concept is called the Trolley Problem. (If you know nothing else about moral philosophy, you should, at bare minimum, be familiar with this classic chestnut.) That thought experiment questions attempts to solve ethical dilemmas with simple math.

On the face of it, actions that produce the greatest good for the greatest number seem preferable to the alternative, and utilitarianism has many followers (even if they never knew the name of their value system). The simplest criticism is rooted in the concern that only the ends are considered, not the means. I would also add that rarely is “the greatest good” a quantifiable attribute, and “the greatest number” is also subject to context (e.g. only humans count?) Utilitarianism diminishes more qualitative ethical impulses, and can also lead to viewing humans as somehow separate from (and superior to) other aspects of Nature—to our detriment. Add up all of these conflicts, put them on an exponential growth curve, and you have a value crisis.

Describing our present predicament as a value crisis is apparently a unique nomenclature, but similar ideas (“behavioural crisis”) have popped up in recent times. Perhaps the concepts have the potential of importance, perhaps not. However, I do not understand why the specific conflict between quantitative (number-based) value systems and qualitative value systems has not been described in any of the literature that I have found to-date. These (or equivalents) are not even terms that appear in the vocabulary, even though number-based values are not a difficult concept to grasp, and their distinction from qualitative values (like happiness, integrity, empathy, etc.) should quickly follow.

The ideas of Frederick Soddy were largely ignored 100 years ago, but are now considered foundational to the field of ecological economics. Who knows? Perhaps someone more qualified than I will adopt and champion some of my ideas in the future. With your vitally essential moral support, reader, I will continue to share. (I don’t ask for financial support. It’s not about the money… ;-)